Does 2018 rhyme with 2000?

A discussion by Hugh MacNally, Chairman and Founder of Private Portfolio Managers

While history doesn’t necessarily repeat itself it does tend to rhyme. With that thought in mind we would like to look back to the end of the 2000 dotcom bubble and see if there are any parallels that might be drawn to the current valuation of internet stocks.

Let’s recap with an article from Denis Taylor then of the San Jose Business Journal (not perhaps a household name but San Jose was at the epicentre of the Dotcom world). Dennis writes on 20 March 2000:

One trillion dollars.

That’s how much at least one analyst believes Cisco Systems Inc. will be worth in a few years–and you’d be hard pressed to find anyone to disagree…

Thirty-seven investment banks recommend either a “buy” or a “strong buy.” None recommend a “sell” or even a “hold.”

George Kelly, an analyst with Morgan Stanley Dean Witter in New York who took Cisco public a decade ago, is one of the Cisco bulls. Cisco’s stock is trading at roughly 120 times Mr. Kelly’s earnings’ estimate of $1.13 per share….

Paul Weinstein, an analyst with Credit Suisse First Boston, believes a $1 trillion market capitalization (stock price multiplied by shares outstanding) is within reach in a few years. He said Cisco’s stock has increased 1,000 times, a perfect 100 percent annual return since it launched its IPO in 199o.

“We humbly submit that over the next two to three years, Cisco could be the first trillion dollar market cap company–and don’t think they wouldn’t love it,” Mr. Weinstein wrote in his “strong buy” recommendation….

Michael Neiberg, lead analyst in the communications equipment sector for Chase Hambrecht & Quist in New York, said Cisco is turning a lot of investors long-term.

“If you had picked a price point to sell [high] at anytime in the past 10 years, you would have been wrong,” he said. “They have such an impressive track record of growing … that the financial community isn’t thinking in terms of a multiple of what they’re earning this year, but what they will be earning three or four years down the line.”

(San Jose Business Journal, 20 March 2000).

Within a month of this article being written the Nasdaq Index (which was heavy in tech stocks) had dropped 35% on its way to a 50% decline by the end of the year 2000. This article is used as an illustration of how perspective can be lost during a boom, where upward stock movements reinforce views and a circular argument develops until unexpectedly the story get clay feet.

Cisco Systems, which was at the time the largest company in the world by capitalisation, eventually fell to 20% of its former capitalisation and its share price is yet to get close to the former peak. However, the business continued to grow and the company is still one of the blue bloods of the tech sector. Importantly, when it went into PPM portfolios 15 years after its glory days we bought it on about 9 times earnings rather than 120 times (which was at the time thought attractive by 37 investment banks!). We are using this example to highlight that extraordinary valuations usually disappoint when the law of big numbers comes into play.

Cisco Systems, which was at the time the largest company in the world by capitalisation, eventually fell to 20% of its former capitalisation and its share price is yet to get close to the former peak. However, the business continued to grow and the company is still one of the blue bloods of the tech sector. Importantly, when it went into PPM portfolios 15 years after its glory days we bought it on about 9 times earnings rather than 120 times (which was at the time thought attractive by 37 investment banks!). We are using this example to highlight that extraordinary valuations usually disappoint when the law of big numbers comes into play.

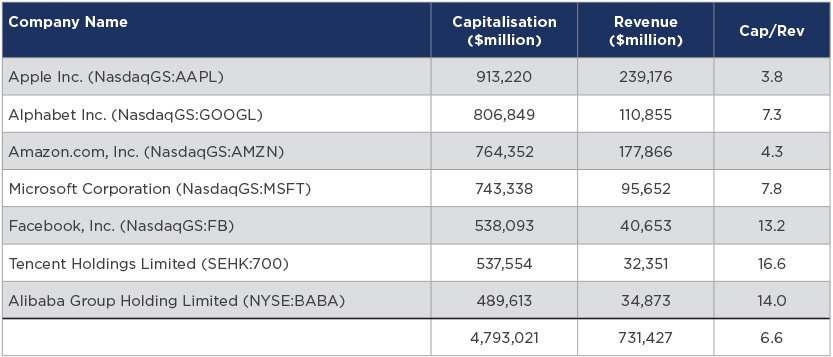

We would like to point to the astonishingly large current capitalisation levels in the tech sector—below is a table showing the market capitalisation (that is the value the stock market gives a company) of the seven largest tech stocks. Currently they are capitalised at a tad short of $5 trillion, but only have revenue of $730 billion or to put it another way their market valuation is an average of 6.6 times their revenue. Given the size of these numbers it stretches credibility that the revenue can grow sufficiently in order to bring these companies back onto more normal valuations within a reasonable timeframe. And that is the point at some stage extreme situation may become too extreme and with a sudden realisation of the incredulity of the situation. This usually occurs when market prices start to slip and the joy of buying something that seems to perpetually go up turns to a question of is it really worth that much.

Who would be buying these stocks at such prices? Maybe the ETFs and Index Funds might have the answer but they don’t look at the fundamentals.

Could it be that in a few years from now we will be able to buy Amazon on the same multiples as Wal Mart and at a price of say $300 not its current $1500?

History would suggest that this is quite possible and at this price it might make sense to us.

PPM’s approach is to buy stocks at valuations that relate to the underlying returns the company can generate and this has meant that we have not bought Facebook or Netflix etc. We recognise that these are great businesses but we think the prices are too high to produce an attractive return for investors. PPM’s investment philosophy has minimised the impact to our clients portfolios from these large and detrimental valuation movements in the past and we believe will puts our clients in a strong long term investment position.

In the next issue we will look at banks globally and locally to see where we think the value lies.

PRINT THIS ARTICLE